The prominent director made his debut in 1967, and since then he has devoted his life to chronicling the common world around him in his own patient, unblinking, and highly humanistic style: “I’m interested in the various ways in which people try to help each other,” you said.

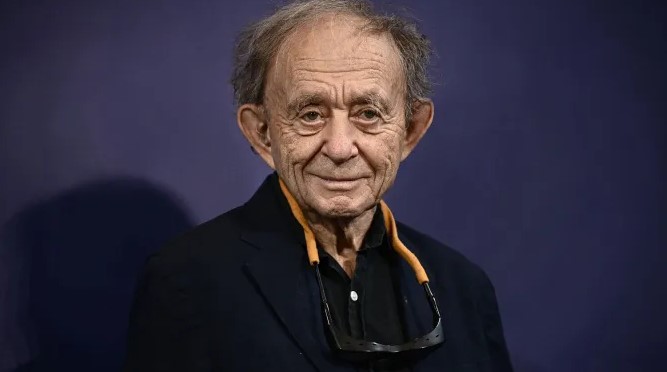

There is a lot going on with Frederick Wiseman. He never has any free time. Wiseman has been working nonstop ever since he directed his debut movie, Titicut Follies, in 1967, when he was 38 years old, which is considered to be a rather late start in the film industry. At the age of 93, he is showing no signs of slowing down despite the fact that he has produced roughly one film every year, a total of 49 to this point (the 50th, Menus Plaisirs — Les Troisgros, a depiction of a French Michelin three-star restaurant, will have its world premiere at the Venice Film Festival on September 3). “I enjoy being productive. My salvation and my religion are both found in my work.

Wiseman’s work has consisted of the development of a succession of cinéma vérité documentaries for the past half of a century. The films’ almost absurdly generic titles, such as High School, The Store, Welfare, Law and Order, and City Hall, belie the films’ intricate and unique portrayals of American institutions. Titicut Follies, an exposé of the inhumane treatment of patients at a Massachusetts asylum for the criminally insane, is still a painful, terrifying watch. They can be funny, like a scene in Zoo (1993) in which a group of female surgeons castrate a wolf as a male attendant stands by, fidgeting nervously; or they can even be inspirational, like his vibrant depiction of a New York cultural melting pot, In Jackson Heights (2015).

He never makes an appearance onscreen because, as he explains, “I’m not very narcissistic,” yet it is easy to recognize when you are watching a film directed by Frederick Wiseman. His method, which was already established in Titicut Follies, is to portray a succession of scenes from the day-to-day lives of a group of people or an institution without any interviews with the camera, without any music, and without any identifying captions or explanatory narration. There is nothing that could be called a conventional storyline, and there is rarely anything that could be considered the primary protagonist (although Boston Mayor Marty Walsh gets close in City Hall). Instead, the location itself – the University of California at Berkeley in Berkeley, California — played a role. The protagonist in each of these stories — the university of Berkeley in At Berkeley, the welfare office in Lower Manhattan in Welfare, and the New York Public Library in Ex Libris — is described as an institution. When viewed as a whole, Wiseman’s films provide a panopticon view of the social structures of the United States, how they function, and the impact they have on individuals.

The “direct cinema” method that Wiseman took has had a tremendously significant impact. Titicut Follies is credited as being one of the primary sources of inspiration for the Academy Award–winning filmmaker Laura Poitras (Citizenfour, All the Beauty and the Bloodshed). Alice Diop, who is known for her films Saint Omer and We, has stated that Frederick Wiseman’s documentaries inspired her to pursue a career in documentary filmmaking. Wiseman’s films frequently give a platform to underrepresented groups. Law and Order (1969), which he directed, has been cited as an inspiration by the Safdie brothers.

The director has made a habit of spending time in Venice. At Berkeley, In Jackson Heights, Ex Libris, and City Hall all made their world debuts at the Biennale, as did Wiseman’s first narrative feature film, Un couple, which debuted there the year before. He is a true Lido legend who is still active today. But up until very recently, Wiseman was known in the television industry as a director. The vast majority of his films were created through PBS and were almost never seen anywhere other than on television. (He is the recipient of three Emmy Awards; in 1969, he won one for Law and Order, and in 1970, he won two for Hospital.)

According to Wiseman, “it’s only in the last 20 years or so that some of the major festivals have shown interest in my films.” “But Venice has been particularly interested, and Venice played an important role because, unlike some of the other major festivals, they show documentaries [in official competition].” “But Venice has been particularly interested,” and “Venice played an important role” They have shown a great deal of interest in the job that I do.

It is possible that the current Wiseman renaissance can be traced back to 2014, when Venice honored the director’s body of work by bestowing upon him an honorary Golden Lion.

“That really helped help boost the theatrical showing of my films,” he says. “I am very grateful for that.” “Other festivals took an interest, and distributors began bringing the films to theaters,” the author writes.

Finding many of Wiseman’s works can still be challenging in some cases. It wasn’t until 2007 that he started selling some of the films on DVD, and in the United States, you won’t be able to see them on any streaming platform other than Kanopy, which is a specialized on-demand service designed specifically for public and academic libraries. The fact that the director shot all but one of his movies on 16 millimeter film and pieced them together using an obsolete flatbed editing machine hasn’t helped matters either. He didn’t start shooting and editing on digital equipment until 2009, when he made La Danse, a documentary on the Paris Opera Ballet. La Danse is a portrait of the company.

When he spoke with THR, Wiseman was in the midst of scanning all of his past films to generate digital prints for cinemas, festival retrospectives, and yes, even streaming. This was in between finalizing the edit for Menus Plaisirs and kicking off the film’s fall festival tour.

Because of his work ethic, Wiseman doesn’t have much time for introspection. However, while rewatching movies that he hadn’t seen “for 40 or 50 years, since I finished them,” he recognized recurring motifs throughout his body of work.

“In a lot of my movies, you’ll find that I’m interested in a lot of the same subjects. My curiosity lies in the various approaches individuals use to assisting one another. He says, “I’m interested in the complexity of human behavior, and I’m interested in the relationship between men and animals.” “However, none of this was done in a systematic manner. I basically have a general notion floating around in my head of a range of topics that I am interested in learning more about, and then I end up learning about those topics while I am making the video. Simply because I never bother to perform any kind of investigation. My study consists of actually making the movie.”

Early on, we settled on the idea of depicting several types of institutions, such as a welfare office, a mental hospital, a high school, and a state legislature.

“I was sick of watching movies and documentaries about famous people,” he recalls. “I wanted to see something else.” “Everyday life has always been something that has fascinated me. And I realized that I could look at your everyday experiences through the lens of public institutions as a framework for doing so. This is a topic that could go on forever. A hospital, a high school, and a police agency are examples of institutions that may be found in every civilization around the world. Every society has its own judicial system, as well as its own theater and dance groups, each of which specialize in different forms of expression.

Wiseman’s strategy consists of embedding himself in the institution for a number of weeks, and sometimes even months, while filming an enormous amount of material – “it’s usually between 100 and 140 hours.” At Berkeley was around 250 because I went to a lot of classes and professors talk a lot” — which he then whittles down to a mere three or four (or nearly six, in the case of Near Death, his 1989 film on critically sick patients in Boston’s Beth Israel hospital) — which he then uses as the basis for his films.

“The very first thing that I do is search for situations, for examples of the activities that take place at the location. I’m looking for something dramatic to happen, anything that will shake me up. I’m looking for anything funny to read. “I’m looking for a wide range of examples of different kinds of human behavior,” he says. “[I’m] looking for a wide variety.” “And I’m looking for sequences that work,” she continued, “so if I’m lucky enough to have captured the right sequence or if I can edit it correctly, the literal scene can expand into a more general or abstract question about human behavior in relation to the place that’s offering the services.”

Wiseman moments can be frightening — Hospital has a two-minute take of a patient throwing up; in Law and Order, we watch as a white plainclothes detective chokes a black sex worker during her arrest — but they can also be spellbindingly commonplace or even banal. For example, Hospital has a take that lasts for two minutes and shows a patient throwing up. Fans of Wiseman have a running joke that he absolutely, positively adores attending meetings. The closest thing the director has to a signature shot is a group of people assembled in a room, discussing — or avoiding discussing — the business of the organization at which they work.

Wiseman states that “I don’t think it’s because I have a particular fondness for meetings,” but that “meetings are important for the life and decision-making in the institutions that are subject to the film.” If you were making a movie about the New York Public Library, for instance, you should know that every week the senior offices held a staff meeting, and a lot of important choices were discussed and decided upon during those meetings. Because, among other things, I’m interested in how choices are made and how power is exercised, it would have been a mistake for me not to attend and include those meetings in my research.

Although Wiseman’s films do not have overt politics in the vein of Michael Moore’s work, his films do feature a strong ethical sensibility that runs throughout them. “I don’t think mine or anybody else’s films are objective, because they represent choices that I’ve made,” he has said, “because they represent choices that other people have made.” However, he is willing to accept the term “fair” to describe his films. “I believe that the experience I had while making my films is accurately portrayed in them,” the director said.

The intense political division that characterizes our day has not had much of an effect on the way Wiseman makes films. The 2018 film Monrovia, Indiana takes a generally sympathetic and oftentimes pleasantly sensitive look at the people who live in a small town with a deep red hue. The novel “In Jackson Heights,” which takes place in the borough of Queens, is a love letter to one of the most ethnically diverse neighborhoods in the United States. He never watches cable news — “all I ever watch on television is basketball or tennis” — and he has successfully disconnected himself from partisan disputes, whether they take place offline or online. After a long day of staring at a screen, he says, “that may sound strange, but you know, after a long day of sitting in front of a screen I am not eager to spend the rest of my time doing so.” “I’d rather go for a walk or read a book,” I’ve often said.

There is not the slightest trace of cynicism to be seen in any of Wiseman’s films, despite the fact that his pictures can be extremely critical of the institutions that they show.

“I think it is just as important to make films that show people making a genuine effort to do a good job as it is to show films or to show experiences where people are being indifferent or callous,” he says. “I think it is important to make films that show people making a genuine effort to do a good job.” “To take two extremes: The prison where I created Titicut Follies was a horrific place, so the picture depicts the incompetence of psychiatrists, the inadequate education and training of the guards, and the horrible conditions in which the convicts are confined. The other extreme is that the prison where I made Titicut Follies was a wonderful place. My sense of what went on in City Hall is that Boston Mayor Marty Walsh had a genuine desire in delivering as good of services as possible to the inhabitants of Boston, and the sequences in the film illustrate the sincere effort to do a good job. This is why City Hall is the opposite extreme because of my impression of what went on in City Hall. I think it’s just as necessary to demonstrate that kind of activity as it is to show apathy and cruelty. At least, that’s how I see it.

After fifty films, Wiseman has no intention of hanging it up anytime soon. If he has anything to say about it, Menus Plaisirs will be his most recent film to be shown in Venice, but it definitely won’t be his last.

“Working is a part of my daily habit, and I enjoy working so I can maintain this routine. It’s a good way to kill some time. I’m probably in denial about how old I am; I still have the impression that I have many more movies to make. I don’t put much thought into things like my legacy or things of that nature. Whenever I’m not doing that, my mind wanders to the next movie. And it would be lovely, even after I’m gone, if my films are still exhibited.”